If state authorities wantonly let violent mobs target innocents, citizens need to resolutely demand accountability and fundamental reforms

The savage carnage in many parts of Gujarat that followed the horrific torching of a railway compartment in Godhra on February 27, 2002, and the systematic and wanton subversion of all civilised norms of relief and rehabilitation of the survivors in the bleak months that followed, witnessed the collapse and perversion of the state machinery to an unprecedented degree.

In the aftermath of the grim and bloody birth of a dismembered Indian nation in 1947, the leaders of the struggle for Indian Independence had resolved to retain a powerful bureaucracy inherited from the colonial legacy of governance. Their expectation was that it would act as a sturdy bulwark, a ‘steel frame’ to strengthen the unification of a vast, diverse, volatile land. In the decades that elapsed after Independence, whereas the trappings of colonial power, incongruous in an impoverished democratic country, were retained and elaborated, a slow but steady decline set in, with the growth of indifference, unaccountability, corruption, sloth, arrogance, and most dangerously, complicity and partisanship.

Beginning with the shameful complicity with mass violence in the anti–Sikh riots of 1984, the decline became precipitous with the ascendancy of fundamentalist pseudo-religious militant ideologies in the country. Sections of the police, civil and military administration bared their active sympathies with these divisive ideologies, while the large majority opportunistically aligned with these to advance their careers.

As a result, the corroded ‘steel frame’ dissolved and in the ‘laboratory’ of Gujarat in 2002, the country witnessed its complete ignoble collapse. The state authorities in Gujarat not only actively connived with a planned and orchestrated massacre of a section of the population, specially targeting hapless women and children. In the months that followed, it abetted and assisted for the first time in the country’s history, the deliberate subversion of all civilised norms of relief and rehabilitation of the

survivors.

In other words, it enabled and assisted not only the murder, rape and plunder of legions of innocent people and their properties. It went further to assist the ruling political class of the state in preventing the organisation of even elementary temporary shelters with basic facilities in relief camps, or grants and loans to assist the destitute and bereaved survivors to rebuild their shelters and livelihoods. This brazen, merciless treatment, with state abetment, of victims of mass violence like unwanted diseased cattle, or like enemy populations, marks a new low in the governance of this nation. It heralds the completion of the unresisting transition of the civil and police administration from protectors to predators of the people.

The culpability of the higher civil and police services in the crimes and inhumanity of the Gujarat carnage and the dishonour of its aftermath, is greater because it is a vocation whose central calling is the upholding of justice, of law, order and the protection of vulnerable people. Default in the performance of one’s duty by a civil or police officer in a riot is not only the crime of a citizen who turns one’s face away from injustice, because of indifference, fear or complicity. It is a crime of much graver magnitude, akin to that of a surgeon who wantonly kills his patient on the operation table.

Until the 1980s, there was an unwritten agreement in our polity that even if politicians inflamed communal passions, the police and civil administration would be expected to act professionally and impartially to control the riots in the shortest possible time, and to protect innocent lives. There were several failures in performance, and minorities were targeted in many infamous riots, but the rules of the game were still acknowledged and in the majority of instances adhered to, which is why the higher civil and police services were regarded to be the steel frame vital to preserve the unity and plurality of the country.

The 1980s saw the breaking of this unwritten compact which has led to the corrosion and near–collapse of the steel frame. It became frequent practice for the higher civil and police authorities to be instructed to actively connive in the systematic slaughter of one community, and to do this by delaying, sometimes by several days, the use of force to control riots. Local state authorities complied, and rioters were unrestrained by state power in their mass murder, arson and plunder.

Why is the decisive and timely use of state coercive force — lathis, tear-gas and bullets by police, para–military and military contingents — so vital a duty of the state in a communal situation? In every other kind of public disorder – labour, student or peasant protests – the broad consensus across a wide section of liberal opinion is that a democratic state must apply the principle of minimum necessary use of force to restore public order and security, respecting the right of democratic dissent

and the expressions of public anger against perceived injustices and grievances.

In situations of sectarian violence, by contrast, the responsibility of the state is completely different from any other. A humane and responsive democratic government must apply in all such situations — of communal riots, or violence against minorities or dalits — the principle not of minimum necessary application of force, but instead the responsible but maximum possible use of force that the state can muster in the shortest possible time. This is because unlike other expressions of public anger, communal violence targets almost invariably people who are most vulnerable and defenceless, it is fuelled by perilous and explosive mass sentiments of irrationality, unreason, prejudice and hatred, and its poison spreads incrementally over space and time. Its wounds do not heal across generations. The partition of our country continues to scar our psyche half a century after its bloody passage. A whole decade of terrorists in Punjab traced their origins to the maraudings of the 1984 rioters. As I held on my lap a six–year–old boy in a camp in Ahmedabad who described the killings of his mother and six siblings, I felt broken by his pain that can never heal, but wondered at the same time how he would deal with his anger when he grows up. Likewise, the ashes of the horrific burnings in Godhra will stir up their own poison. But it is important to understand that the cycles of hatred did not begin in the railway compartments of Godhra, and they will not end in the killing fields of Gujarat.

It is for this reason that every moment’s delay by state authorities to apply sufficient force to control communal violence is such an unconscionable crime: it means more innocents will be slaughtered, raped and maimed, but also that wounds would be opened which may not heal for generations.

Civil and police authorities today openly await the orders of their political supervisors before they apply force, so much so that it has become popular perception that indeed they cannot act without the permission of their administrative and political superiors, and ultimately the chief minister. The legal position is completely at variance with this widely held view. It is unambiguous, in empowering local civil authorities to take all decisions independently about the use of force to control public disorders, including calling in the army. The magistrate is not required to consult her or his administrative superiors, let alone those who are regarded as their political ‘masters’.

The law is clear that in the performance of this responsibility, civil and police authorities are their own masters, responsible above all to their own judgement and conscience. There are no alibis that the law allows them.

It may be argued that this may be an accurate description of the legal situation, but the practice on the ground has sanctified the practice of political consultation before force is applied. Only to convince the reader that I speak from the experience of myself handling many riots, I could contest this with my own experience in the major riots of 1984 and 1989, where as an executive magistrate I took decisions about the use of force and calling in the army, without any consultation. I could similarly contest this with the experience of many other women and men of character in the civil and police services across the country, who would similarly testify to salutary application of force, to control more difficult communal violence, without recourse to political clearances. There can be no dispute that given administrative and political will, no riot can continue unchecked beyond a few hours.

However, I will not substantiate this with my own experience, or those of older officers. It gives me great pride and hope, amidst the darkness that we find ourselves in today, to talk of the independent action taken by a few young officers in Gujarat and neighbouring Rajasthan during the present crisis itself.

The culpability of the higher civil and police services in the crimes and inhumanity of the Gujarat carnage and the dishonour of its aftermath, is greater because it is a vocation whose central calling is the upholding of justice, of law, order and the protection of vulnerable people.

Rahul Sharma was posted as SP, Bhavnagar for less than a month when the Godhra killings and the subsequent rioting all over Gujarat happened. Following Godhra, he deployed a strong police contingent for the Gujarat Bandh called by the VHP the next day, February 28. Unlike the rest of Gujarat, the day passed off without much trouble in Bhavnagar. But the next day, Rahul learned that a mob of around 2,000 men armed with swords, trishuls, spears, stones, burning torches, petrol bombs and acid bottles, was about to attack a madrassa with around 400 small Muslim boys between the age of 12 and 15.

Rahul rushed to the spot where there was a police force of around 50 people. Seeing that the force was hesitant to open fire on the armed mob, Rahul himself took the rifle from a fellow constable and opened fire. As some attackers fell to police bullets, the crowd stopped in its tracks and faded away.

Rahul then made an entry in the logbook saying that he had fired from the constable’s gun to save the lives of the children. He also gave an order that any policeman with a gun not opening fire to save human lives from a violent mob would be prosecuted for abetting murder. This gave a clear signal to the police force that the SP meant business, was willing to take full responsibility for his actions and was prepared to stick out his neck however far.

This had an immediate effect on his force, and Bhavnagar was a town where more rioters were killed in police firing than innocent victims in actual rioting. For this, Rahul was moved out from Bhavnagar in a mere month of his assuming charge. He is quoted in the Outlook as saying, “I’m not one to run away from transfers. I take these things in my stride. Other than controlling the riots, I did no mischief.”

In neighbouring Rajasthan, the superintendent of police of Ajmer, Saurabh Srivastava, with a young SDM in his first charge and his small force, doused communal fires in Kishangarh on March 1, 2002, which had the potential of inflaming the tinderbox of the entire state. They controlled an enraged armed mob of over a thousand men bent on attacking minorities in a pitched battle for over four hours.

Another defence that we are hearing is that the lower police force has become hopelessly charged with the communal virus; therefore it is impossible to deploy it as a non–partisan instrument of coercive force to control rioting. It is true that our men and women in khaki work under conditions of great stress, long hours, inadequate facilities and uninspiring training. Even so, whenever commanded by leaders of character, who are non–partisan, professional, fearless and lead from the front, the same forces are known to protect peace admirably.

Unlike the statutory duties and powers of state authorities in the control of public disorders, which are clearly codified in the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, there is no comparable codification of their duties for extending relief and for rehabilitating to the survivors of sectarian violence or natural disasters.

However, even though there is no formal codification, the principle that underlies the state responsibility in such situations, and the practice even of the colonial government in pre–Independence days, which has been strengthened further by Relief Codes, government circulars and practice after Independence, is that in any natural and human-made disaster, including riots, the state government is the primary agency responsible to provide relief, succour, security and rehabilitation to the victims of such disasters.

It may seek the assistance of NGOs in these tasks, but it cannot be allowed to abdicate its own central responsibility to NGOs. Therefore, the state government must take direct responsibility not only for the food, but also the safety, shelter, protection from the extremes of climate, health, psycho–social support to deal with their trauma, sanitation, education and rehabilitation of all the children, women and men housed in its camps, and affected by the mass violence.

In Gujarat, the overwhelming majority of camps were set up, and continue to be run, not by the state but by self–help efforts of the Muslim community. The few Hindu camps, mostly housing people living in Muslim dominated areas who feared reprisal attacks, were similarly run by Hindu organisations, although with more conspicuous state support.

There can be no dispute that given administrative and political will, no riot can continue unchecked beyond a few hours. However, I will not substantiate this with my own experience, or those of older officers. It gives me great pride and hope, amidst the darkness that we find ourselves in today, to talk of the independent action taken by a few young officers in Gujarat and neighbouring Rajasthan during the present crisis itself.

State authorities maintain that it is the culture of Gujarat that NGOs establish and run relief efforts. It is euphemistic to describe the support for most camps as even coming from NGOs, because like the state, the majority of mainstream NGOs which were so active in the relief and reconstruction work after the killer earthquake in 2001, have chosen to distance themselves from healing and rebuilding in this far more politically volatile human tragedy.

The result is that in practice, camps are running substantially on the strength of self–help efforts of the affected communities. These self–help efforts even amidst so much adversity inspire great admiration, but this does not absolve the state of its direct and central responsibility that basic living conditions and services are ensured in the relief camps. If, for instance, epidemics break out in the camps, state authorities rather than the camp managers, must be liable.

After an average of ten days subsequent to the violence, state authorities commenced the supply of basic rations to the camp, along with a grant of five rupees per head per day to cover costs of cooking etc. The food is prepared and served in orderly shifts by volunteers from among the camp residents. However, resources are required for much more than just food, in running such populous relief camps of devastated people.

Our deep worry remained unaddressed that if resources from relief did not come from the state, donor and aid agencies or NGOs, an impoverished, hapless and gravely threatened community would increasingly find itself thrown into the hands of either the mafia or fundamentalist leaders.

Camp residents, the majority of whom have survived with only the clothes on their backs, need additional sets of clothes, as well as a small allowance for daily expenses. Another matter of grave concern is sanitation. In most camps, the number of available toilets and bathing places is abysmally less than needed, and camp authorities find it difficult to ensure the cleanliness of the toilets.

Whereas this compromises the privacy of the residents, especially women, an even more serious worry is that failures in sanitation, particularly after the rains break out, have the potential of causing epidemics. We need to establish some minimum

acceptable ratio of toilets and bathing spaces at all camps, and arrangements for their cleanliness.

Camps, temporary homes to often several thousand children, women and men, are organised mainly in dargahs, schools or graveyards. The majority of residents live in open shamianas. Makeshift canvas covers were the only protection against the blazing summer heat. However, the survival of the camps and its hapless residents was most threatened by the on–coming monsoons. The camps were low–lying, with tattered canvas covers, no match for the monsoon rains.

Activists attempted to alert the state government about the special vulnerability of the residents of the camps during the monsoon rains, and their desperate need for rainproof shelters. However, efforts through the courts, the National Human Rights Commission and the national media failed to secure state action to construct these shelters.

Finally, three weeks before the outbreak of monsoons, when it became clear that the survivors in the camps would be unprotected from the fury of monsoon rains, a few local organisations decided to build the rain–proof shelters themselves. With volunteers deployed from across the country, rain–proof shelters were constructed with plastic, canvas and bamboo scaffoldings. This massive effort has succeeded in preventing the forced distress dispersal of the most destitute survivors who still remained in the camps.

In Gujarat, the overwhelming majority of camps were set up, and continue to be run, not by the state but by self–help efforts of the Muslim community. The few Hindu camps, mostly housing people living in Muslim dominated areas who feared reprisal attacks, were similarly run by Hindu organisations, although with more conspicuous state support.

Civil rights activists and organisations failed to pressurise the state government also to ensure minimal standards of sanitation and clean drinking water, public health and education. Directions of the National Human Rights Commission and outrage in the national media was resolutely ignored by the state government, which refused to provide much more than ration supplies, occasional visits by doctors and grants to run some temporary schools in camps.

It is indeed tragic that such large numbers of citizens are forced to subsist in refugee camps, reminiscent of the camps after Partition, for extended periods. The residents of these camps, who are forced to live without work or personal spaces in very austere physical conditions, long to return to normalcy. But they can be expected to do so only if they feel secure and have the resources for rebuilding their lives. The neglect of these will prolong their agony, but to force the pace of their exit from the camps without this will threaten their very survival.

After the monsoons broke out, the state government has mercilessly stopped even the supply of rations to the majority of the camps. The district authorities have served notice to the camp residents that the camps are unauthorised, there would be no provisions for food or visits by medical teams. The notices pasted in various camps ominously add that the state government would not be responsible if any calamity or áafat befalls the camp.

District authorities maintain that they want to relocate the camp residents to three large camps. But they are unable to explain how several thousand more women, children and men can be accommodated in these camps, when there continue in these camps sub–human facilities even for the original residents. In the absence of rain–proof shelters and sanitation, crowding these camps further would further mount their distress.

The residents themselves are unwilling to be shunted like unwanted cattle. However hard life is in these camps, at least they are close to their old homes and some have been able to find casual work. Virtually unassisted, they have courageously commenced their uphill journey to rebuild their lives. It would be unconscionable for state authorities to make this journey even harder.

However, despite written assurances to the National Human Rights Commission and the Gujarat High Court, as well as discussions in the presence of the Prime Minister with a delegation of concerned citizens led by IK Gujral, state authorities persist stubbornly with their pitiless enterprise to close camps and to starve them even of food supplies.

The survivors of the mass violence are facing insurmountable difficulties to secure even the meagre compensation that is assured by circulars of the government. Many of these problems are built into the design of the instructions; others are the outcome of openly partisan implementation by state authorities.

The government of Gujarat has announced a death compensation of Rs.1 lakh for every person killed in the riots, and the Prime Minister has announced an additional support of Rs. 50,000. The first difficulty here is that this support is available only on the production of a death certificate. However, the overwhelming majority of the victims were so badly burned that they could not be identified. The problem was further aggravated by the turbulence created by the mass violence that separated the survivors from their dead.

In these circumstances, it is not acceptable that the unidentified dead should be legally treated only as ‘missing persons’, which would mean in effect that the survivors would be eligible for compensation after the lapse of maybe seven years. Instead, a sympathetic state administration could have developed alternate mechanisms to verify deaths. For instance, an application and affidavit by the next of kin, supported by five affidavits by neighbours or observers, could be accepted. This may be corroborated by documents like the 2001 census, voters’ list, ration card or birth certificate.

Even if the authorities feel that more evidence is required, death compensation should be sanctioned based on prima facie evidence to the next of kin in the form of bonds that can be redeemed only after the investigation is concluded. However, in the meanwhile, it would ensure that the next of kin is able to subsist on the interest.

The large majority of camp residents are impoverished casual workers, artisans, industrial workers, petty traders or members of their families. There are other more wealthy survivors of the mass violence who have lost their business establishments or factories, and they are mostly not in relief camps.

Given that the numbers of damaged business establishments, small and large, run into tens of thousands and are spread across the state, and that the losses amount to thousands of crores of rupees, the challenges of rebuilding the lost livelihoods of the survivors of mass violence is extremely daunting. It would require the mobilisation of enormous resources of government, financial institutions, aid agencies and the private sector.

Existing instructions of the government of Gujarat, dating back to 1989, provided for financial grants up to Rs.10,000 for riot victims who have lost their earning assets. The new norms recently issued by the state government provide for assistance up to Rs.10,000 based on actual damage of movable and immovable earning properties.

According to a report by an NGO, Disha of Wadali Camp in Dahod, most people have received housing compensation of as little as Rs. 200 to Rs. 500. It would be impossible to rebuild even a mud and thatch hut, let alone equip a house with these levels of ‘compensation’.

This ex–gratia assistance expressly debars the riot victim from seeking loans and subsidies under other schemes of the industry department. The ex–gratia relief that riot victims will receive is likely to be much less than the full resources required by the riot victims to rebuild their lost livelihoods. Therefore, the provision debarring recipients of ex-gratia relief for securing benefits of other government schemes is an unprecedented and merciless innovation, a perversion of the obvious principle of humane governance that the state government should make special efforts to secure the access of the riot victims to receive assistance to rebuild their lost livelihoods, by a convergence of all government schemes in a single window.

An even more daunting challenge is the reconstruction of shelters of almost two lakh persons rendered homeless overnight because of the mass violence. Homes have been looted, stripped bare of their belongings, damaged and burned by marauding mobs.

The Prime Minister announced an ex–gratia assistance to families whose houses were damaged or destroyed at Rs. 50,000. Instructions of the state government fixed the assistance up to Rs 50,000. Evaluation teams of only government functionaries have tended to work entirely without transparency and empathy, or even technical rigour, and average house compensation paid has been around Rs 5,000.

Surveys by NGOs have found that evaluation teams have fixed housing compensations at very low levels, even well below the already low ceilings. A report of the Citizens Initiative states, for instance, that in Sankalit Nagar, Juhapara, Ahmedabad, of 67 houses burnt completely, 13 houses have received compensation between Rs.1,000–2,000; 18 have received compensation between Rs. 2,000–5,000; another 18 have received compensation between Rs. 5,000–10,000; and yet another 18 have received compensation of more than Rs. 10,000. One house has received less than Rs. 500.

According to another report by an NGO, Disha of Wadali Camp in Dahod, most people have received housing compensation of as little as Rs. 200 to Rs. 500.

It would be impossible to rebuild even a mud and thatch hut, let alone equip a house with these levels of ‘compensation’. Teams of evaluation of house damage must include representatives of the riots victims and non-government technical experts, and this must be concluded within one month. Without such assistance it would be impossible for the survivors of mass violence to move out of the camps into their own reconstructed shelters.

Even these grants would be very meagre given the scale of resources that affected families would require to rebuild their homes. It is possible only if there is a massive mobilisation of housing and other financial institutions and a single–window access to their soft loans organised within the camps themselves. The NHRC had suggested the involvement of HUDCO, HDFC and international financial institutions and development organisations for augmenting the vast resources required by the riot victims for rebuilding their houses. This also has not been done.

In this way, in the carnage in Gujarat of 2002 and its aftermath, the state administration has succumbed not only to complicity in the mass violence, but even more shamefully has unresistingly allowed itself to deny tens of thousands of bereaved, destitute, battered innocent women, children and men with the means for their very survival. The journey from state as protector to predator is complete.

It is sometimes also argued that the entire higher civil and police services have become politicised beyond repair, therefore whatever be their legal and moral duties, they today lack the conditions in which they can reasonably be expected to perform them. Once again, I would strongly contest this alibi. I have spent twenty of the best years of my life in the civil service, but always found that despite the decline in all institutions of public life, there continue to be the democratic spaces within it to struggle to act in accordance with my beliefs without compromise. I do not regret a single day. One may be battered and tossed around, in the way that young police officers who opposed political dictates to control the recent rioting in Gujarat were unjustly transferred. But in the long run, I have not known upright officers to be terminally suppressed, repressed or marginalised. On the contrary, I value colleagues, in the civil and police services, usually unsung and uncelebrated, who have quietly and resolutely performed their duties with admirable character and steadfastness. Few in the civil and police services can in all honesty testify to pressure so great that they could not adhere to the call of their own conscience.

It is not that there are no costs, but then if the performance of duties was painless, there would not be many who would fail in the performance of their duties. The costs are usually of frequent transfers, and deprivation of the allurements of some assignments of power and glamour, which are used to devastating effect by our political class to entice a large part of the bureaucracy today.

Today, when I stand witness to the massacre in Gujarat enabled by spectacular state abdication and connivance – or to the national disgrace of the subversion of all civilised norms of relief and rehabilitation – I recognise the cold truth that the higher civil and police services are in the throes of an unprecedented crisis. The absolute minimum that any state must ensure is the survival and security of its people, and elementary justice. If state authorities wantonly let violent mobs target innocents without restraint — or connive with the most cynical and merciless designs to deny them the elementary means for human survival — and they continue to do this with impunity and without remorse or shame, then citizens of the country need to resolutely demand accountability and fundamental reforms.

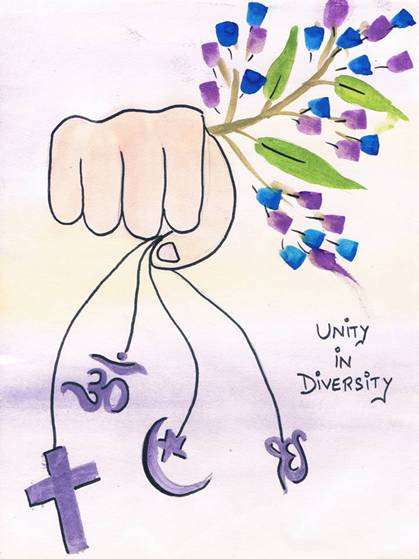

They cannot permit the collapse or subversion of the state, and its metamorphosis from an institution for justice and security, the protection and welfare of the people, into one that victimises as state policy a segment of its population. Too much is at stake: justice, our safety, our pluralist heritage, and indeed our very survival as a humane and democratic society.

Archived from Communalism Combat, September 2002, Anniversary Issue (9th), Year 9 No. 80, Protectors turn predators