Mumbai: A 33-percentage-point gender gap in mobile phone ownership in India is exacerbating inequality and inhibiting women’s earnings, networking opportunities and access to information, according to a new study by the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Strong social norms, customs and individual beliefs create further barriers to access for women already facing the “economic challenges” of owning and operating a phone, said the new study by Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD), a research centre at the Kennedy School.

No more than 38% of women in India own mobile phones, compared with 71% of men. While this figure varies widely across different socio-economic groups and states, the gender disparity in mobile ownership “exists across Indian society” and is not restricted to poorer, less educated groups.

South Asian countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh remain “clear outliers” for gender-equal mobile phone ownership among nations with similar levels of development–comprising some of the highest gender gaps in the world.

“It’s even more of a puzzle when you see usage and ownership is actually much cheaper here [in India] than in sub-Saharan Africa for example,” Rohini Pande, Rafik Hariri Professor of International Political Economy at Harvard Kennedy School, told IndiaSpend.

“If we were able to pull more women into the labour force and enable greater participation, we could see this translate to greater access to resources.”

Improving mobile phone access can increase the spread of information amongst unconnected communities, including up-to-date market prices, job opportunities, and advice on healthcare and financial services.

A persistent gap

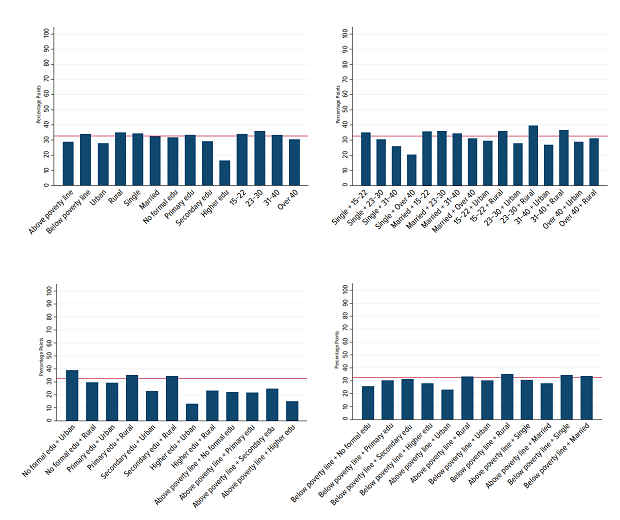

Women consistently trail men on mobile phone ownership and by at least a 10-percentage-point gap in each demographic category.

Variations amongst the sub-population groups highlight the key socio-demographic factors contributing the largest impact on female phone ownership.

For example, rural areas tend to have persistently higher gaps than urban areas.

The gender gap is lowest between men and women with higher education in urban areas at 13 percentage points, yet almost doubles amongst their rural counterparts to 23 percentage points.

There is one exception to this trend, found amongst those with no formal education. In rural areas, the ownership gap was lower at 30 percentage points, compared to 39 percentage points in urban areas.

Mobile Phone Gender Gap, By Poverty, Urbanicity, Marital Status, Education, Age

Source: A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India

Differences in education levels also appear to exert a significant force on the likelihood of mobile phone ownership.

While the gender gap among those with a primary and secondary-level education was 33 percentage points and 29 percentage points respectively, those with higher education had a significantly better gender gap at 16 percentage points.

Below poverty line groups were also found to have a larger gender gap than above poverty line groups (34 versus 29 percentage points).

However, making a simple correlation between increased wealth and reduced gender disparity should be avoided, since a more complex picture emerges when looking at state-wise data.

To some extent, more economically developed states show higher rates of mobile phone ownership among men, indicating that wealth facilitates phone ownership–but some of the largest gender gaps are also found in states with per capita income well above the national average.

Source: A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India

In Karnataka and Punjab for example, where per capita income equals Rs 132,880 and Rs 114,561 (compared with the per capita net national income of Rs 103,219), the gender gap is 37 and 39 percentage points respectively and far behind states with similar per capita income levels such as Gujarat (28) and Maharashtra (29).

One of the lowest gender gaps (19 percentage points collectively) is in the northeastern states, where the disparity between male and female ownership is slightly higher than in both Delhi and Kerala (both 18 percentage points).

Northeastern states, as well as Kerala, have traditionally had matrilineal societies–where descent is traced through the female line and can involve inheritance of property/rights–potentially explaining lower gender gaps and highlighting how community-specific social norms can be more significant than economic development in allowing women access to technology.

The highest gender gaps are found in the northern states of Rajasthan (45), Haryana (43) and Uttar Pradesh (40), states traditionally observed to have the most conservative attitudes.

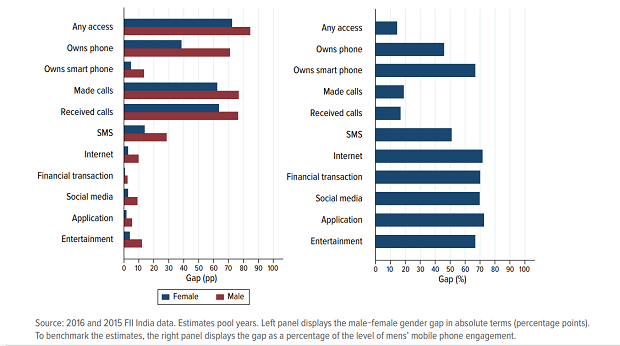

Additionally, wide variations in the way both men and women use mobile phones exists, both in terms of task complexity and whether they borrow or own the phones they use.

As many as 47% of women who accessed a phone were borrowers rather than owners, compared to 16% of men, according to Intermedia Financial Inclusion Insights (FII) data from 2015-2016. Borrowing rather than owning a phone naturally has implications for independence and practicality.

Equally, women are less likely to carry out more sophisticated tasks on a mobile phone, with the gender gap for simple tasks, such as making/receiving calls, at 15-20 percentage points. Even sending a SMS has a gender gap of 51 percentage points. Social media has the widest gender gap at 70 percentage points.

Gender Gap In Basic And Smartphone Features

Source: A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India

The primacy of social norms

The persistence of low female mobile phone ownership, across all sections of society and throughout the course of a woman’s life, suggests none of the demographic characteristics are “the central cause of the gender gap”, the study said.

Instead factors like social norms and levels of empowerment can explain why ownership gaps remain for “even the most equitable sub-populations”.

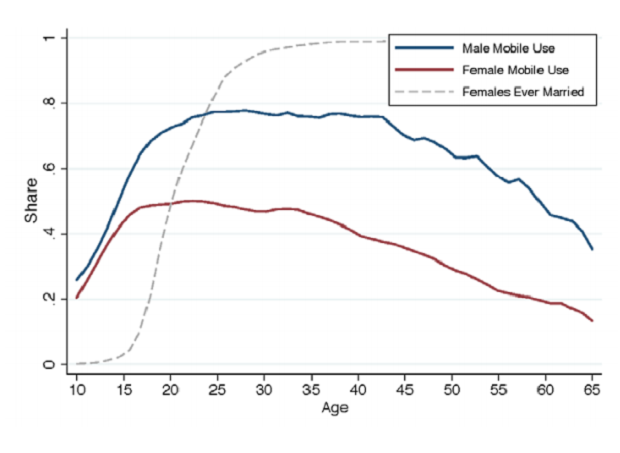

At age 10, around 20% of girls use mobile phones, compared to 27% of boys, according to data taken from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) conducted in 2012.

As adolescents enter puberty, a dramatic widening of the gender gap begins. By age 18, the gap has widened to 21 percentage points and remains in place for the rest of a woman’s life.

Mobile Phone Use By Gender And Age

Source: A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India

Reputation risk, distraction from caregiving duties and rebellion against subservience and patriarchal authority are some of the reasons why families deny or reduce mobile phone access to women, the study found.

The idea that using mobiles phones threatens the preservation of a girl’s purity (particularly important for unmarried young women) is the most prominent barrier to mobile phone access that emerged from the study’s 65 individual interviews, conducted across five states.

While respondents in some regions (rural Madhya Pradesh and some in urban Maharashtra) linked women’s promiscuity to using mobile phones, other respondents were concerned about women being subjected to digital harassment which they had observed in the media (Tamil Nadu, Delhi, Maharashtra, West Bengal).

Communities associate these concerns expressly with female phone usage, rather than male. This is due to the supremacy of preserving a girl’s ‘marriageability’ factor–“inextricably” linked to her reputation–and which is deemed more “fragile” than a boy’s.

Protective parents charged with guarding a daughter’s honour and subsequent marriage prospects ban mobile phone use before marriage or place restrictions (e.g. no uploading pictures to social media or using the phones outside the home), thus leading to a widening in the gender gap during the pre-marriage period.

“When a girl is talking on the phone, they will surely think she is talking to a boy. They never understand that a girl could be talking about her schoolwork,” said one female respondent from Maharashtra.

After marriage, when the parents’ duty is done and the bride has left for her new home, phone ownership is considered reasonable. The newly married woman must be able to keep in-touch with her family and friends, so a phone is often seen as a practical and desirable wedding gift.

Yet swapping one subservient household for another does not necessarily mean barriers to access have reduced, but rather the social pressures in the marital home have replaced those in her natal household.

As “caregivers” women should not be seen to spend too much time on the phone, using it only for “socially-acceptable, ‘productive’” means and focusing on her primary responsibility–taking care of her family and household, the study found.

Empowerment and the way forward

Income and women’s empowerment have similar “explanatory power” as drivers of the gender gap and determinants of mobile phone use, the study said.

Phone usage increased by 10.6 percentage points between the first decile and last decile–data divided into ten equal parts in increasing order–of women’s empowerment, according to an ‘empowerment index’ calculated by analysing female responses to the IHDS survey.

Levels of empowerment were measured by taking a composite average of responses to questions relating to four main themes: Economic engagement, decision-making, mobility and community attitudes.

The empowerment index is the most accurate method available to gauge a community’s perceived norms, since the questions ask women to report what others in their community think and do, according to the study.

The increase in empowerment is similar to that found amongst income decile groups, which registered a nine-percentage-point difference between the first and last decile, indicating that both factors have a similar level of impact on mobile phone ownership

Empowerment and income are inextricably linked however, and policy-makers must consider this when attempting to remove access barriers, the study advised.

Solely targeting the economic challenges of purchasing and running a mobile phone, without considering potentially restrictive social norms, may not be effective.

Measured approaches which reflect on both economic and normative aspects have been successful. Reservations for women and payments to delay child marriage in India is an example where economic incentives have incentivised people to change a societal norm.

If mobile phones can be viewed as “mechanisms to increase rather than threaten” women’s safety and well-being, social attitudes could change, the study suggested.

“Without access to a mobile phone, the most important thing is that you will have a smaller network socially, a smaller network that can help you get jobs and a smaller network that can keep you safe if you’re out somewhere,” said Pande. “Networks are very important for the transmission of information and sharing resources.”

(Sanghera is a writer and researcher with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend