“Racism is taught to us as a western concept, but it definitely exists in India,” said Aditya Panikker, creator of ‘Black Lives in India’ video that discusses the role of racism in casteist hierarchy.

The management professional working in France picked up a camera as a hobby in 2019 and eventually decided to use his talent to discuss social issues in India. His aforementioned video was inspired by the Black Lives Matter Movement in the USA that brought racism to the forefront of international issues.

“I wanted to speak about the Siddi community to remind everyone about the fact that racism exists in India and is very much intertwined with the caste system,” said Panikker.

Panikker said he wanted to do more than ‘performative activism’ and help people understand the complexities within such social evils. His videos provide context to the current socio-political issues to inform people who continue to sit on the fence.

He also thought that upper-caste people in India often fail to realise their privileges. He said that the over-simplistic attitude of “I don’t believe in casteism” is not enough because the system exists regardless, and benefits the upper through its skewed rules.

“We speak against the caste system, but we don’t spend enough time listening to the oppressed. We as upper-castes have a tendency to take the mic and speak on their behalf,” he said.

Instead, Panikker suggested that people at the top of the social pyramid could use their position to start a discourse within their social circles since institutions like schools failed to highlight the severity of the issue.

“Schools teach the caste system as if it is a thing of the past, we don’t have any Dalit literature in our curriculum to show us the real damage done by this social evil. It is taught to us as a form of categorisation and I’ve seen the kids in my 5th-grade class try to identify and compare their place in the society based on their caste,” he said.

He remembered his own experience when he first picked up a book written by Sharankumar Limbale – a prominent Dalit writer – and was appalled to realise how poorly he understood the caste system. Panikker said this was a consequence of the protected manner in which people were taught casteism.

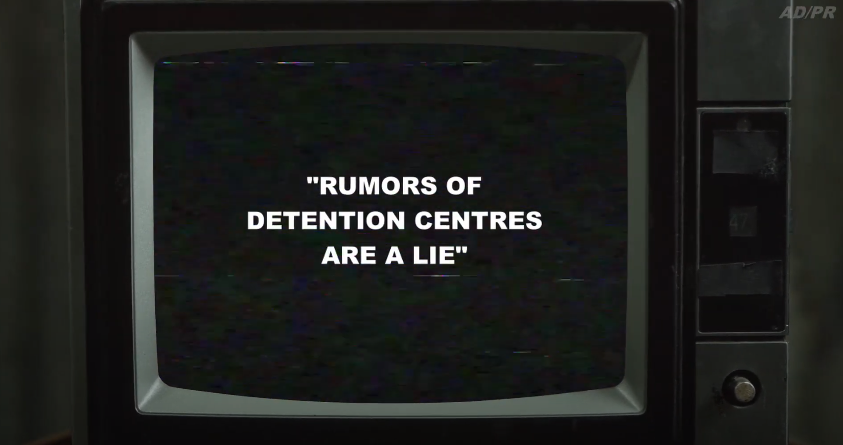

While Panikker’s first video talked about persisting social evils, his latest video talked about detention centres in India with relation to Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) 2019 and the National Register of Citizens (NRC.) He started the research as a personal project while wondering about people who would not be granted citizenship.

“I started reading about these camps and realised that the available information was very scattered and limited,” he said.

Moreover, the little information collected deeply disturbed him. Thus, he decided to make a video that would focus all the scattered information to a single source.

“A lot of people remain neutral about these issues because they don’t have the time to sit and understand them properly. This is also because of the amount of time and research it takes to find reliable sources,” said Panikker.

He hoped that his video would help people take a stand for or against the problem rather than remain silent because he believed, “Our silence only helps the oppressor, not the oppressed.”

According to Panikker, the biggest problem in the country was the manner in which people perceived casteism, islamophobia, religious intolerance. Panikker worried about the growing xenophobia that has created a toxic environment in the country. He also felt this change in perception had occurred since BJP-regime began in 2014.

He pointed out that freedom of speech nowadays is not the same as it was in 2014. Anti-government did not mean anti-India, he said. He observed this censorship for his videos as well. Nonetheless, he tried to engage with the hostile comments so that neutral folks who read the comments section understand both sides of the argument.

Although Panikker noticed that people were scared to publicly share his political videos, he still encouraged artists to create whatever they liked including socio-political issues.

“It’s important as artists to speak for yourself because these issues are going to affect you as well,” he said.

“He could already feel the effects of India’s political condition on his own life in France as he realised people’s perception of the “stereotypical Indian” had changed from a peace-loving person to a more intolerant individual.” Moreover, India’s mainstream media did not help with this perception by focusing on sensational news.

“When talking of mainstream media, we only focus on North India and TV channels that make a lot of noise,” he said, indicating that South Indian media often goes unacknowledged.

Panikker hoped that by using his privilege and talent, he could redirect the attention back to the marginalised and overlooked sections of society, thus effectively “pass the mic.”

Related:

Cleaning up the political mess with artisanal soap?

Contemporary artists raise key questions about freedom of speech and expression

Art and activism are complementary endeavours: Bhawana and Smish