One of the major accusations against the historians in India is that of neglecting and ignoring the role of the marginalised in the freedom struggle. Most of the time, we were ‘informed’ that there were some ‘heroes’ and ‘villains’ of the freedom movement, and then there were historians fighting the ‘political battle’ of ‘history’ and interestingly all of them belonged to the same stock of caste as well as ‘power’ positions as their opponents. None of the them really bothered that a huge country like India will have different take on history or presenting the historical figures.

History is also about events, and not what we personally like or dislike but the fact is history has become the most powerful tool at present to decide our ‘future’. There are claims and counter claims about whose ‘history’ is most authentic, and whose isn’t. But there are vital questions that should be asked:

- Why have been the issues of Dalits and Adivasis been relegated to the back pages of history?

- Why do we deny them agency over what happened?

- Far more importantly, can history be based only on documents, thereby excluding Dalit Adivasi history narratives, recorded in oral traditions?

This is why folk-lore and live stories too become an important tool for understanding history.

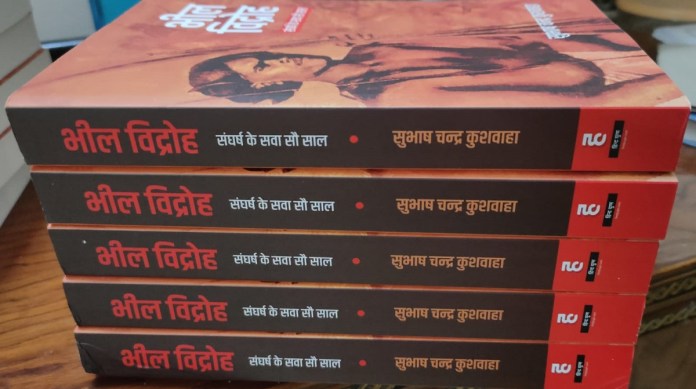

Subhash Chandra Kushawaha has emerged as an extremely important chronicler of the history as far as the issue of the marginalised is concern. He has come out with a book that should be essential reading for all who are keen to further study on the Bhil Tribe. His book: ‘Bhil Vidroh: Sangharsh ke sava sau saal’ (Bhil Revolt: One Hundred and Twenty-Five years of Struggle) has been published by Hind Yugm and is in Hindi. It has chronicled their history of 125 years, and a large part of his documentation has been explained through accessing the historical documents in various archives, both in India as well as abroad.

He has covered the period between 1800 to 1925, which has mostly been covered by international newspapers as well as various documents available in various archives. It is not that the history of Bhils has not ‘existed’ prior to it, but there is a historical truth in the fact that documentation pertaining to that period need to be explored as you might not get it in archives but probably in folklore by visiting those places, speaking to people or even visiting the old monuments, structures, listening to traditional songs or understanding whether there is any celebrations or festivities related to that.

Most of the time, the history of Dalits and Adivasis has been obliterated from our ‘manustream’ history writings projects under the flimsy excuse that the “documents or data are not available”. Subhash Chandra Kushwaha has painstakingly done enormous work in connecting the dots. However it needs more exploration now, as he has started a process which must be strengthened further by reaching out to those places and people about whom the work is being done.

Bhils have been victims of our hierarchical caste system and were brutalised and criminalised by the kingly clans of Rajputs prior to arrival of British, explains the author. Bhils were the owner of Khandesh as well as Central India, but were pushed to forest by the ‘Rajput invaders’. Though reading through an extremely important article written by Captain E Barnes and Thomas Emily Young published in ‘The journal of society of Art’ on February 8, 1907, suggests that Jhabua till 1550 was a Bhil Kingdom passed to Rajputs by Akbar. The whole article is extensively narrative which reflect how the British used the data to understand communities but there was much more than mere data in their work. The 1931 census which was done based on caste, gave ample example of scholarship of the British and attempt to understand India’s diversity through different angles including caste and ethnicity.

Subhash Chandra Kushwaha has built up narrative chronologically and they help us understand the areas where Bhils were residing. One full chapter on Khandesh and Bhils of Khandesh, where both the Mughals as well as Marathas fought to control the Bhils. With the ascendency of Bajirao as Peshwa in 1798, Khandesh saw the down fall of various Bhil Jagirdars and anarchy grew afterwards. It is reported that Peshwas remained the most brutal force who actually criminalised Bhils. Equally brutal were Marathas too. The Bhil Rajput relations are well discussed here in the book but it is also acknowledged that ‘Bhilala’ community of Bhils emerged out of relationship between Rajputs men and Bhil women or vice versa. Bhilala’s considered themselves superior to others because of their lineage but other Bhils don’t think so.

The British felt that the Brahmin rulers of Western India made Bhils what they became at that time due to brutalities and criminalisation of Bhils. The story of anarchy and chaos in Bhil land has been very well described in the book. By 1818, anarchy was it was at its prime when British took control of the Khandesh and had to face 80 notorious gangs (these are not my words but as per the book) with over five thousand followers. The British knew it well that it would be difficult to control the anarchy in Khandesh unless Bhils are taken into confidence. They had realised that the chaos and anarchy in the Bhil zones are basically because of the criminalisation process started by the Peshwas and Marathas so the British focused on the ‘policy of reclamation’ and not on policy of extermination as was during the previous regimes.

By April 1827, Khandesh Bhil corp was born as peace was restored in the region. Mr Kushwaha has explained in the policy of British against the Bhils of Central India and Madhya Bharat in the chapter giving detailed example of how robbery and looting in the region was rampant. It is important to understand why the English felt Bhils could be useful for them as they were brave and loyal.

The chapter ‘Bhil Rebellion in Khandesh and Madhya Bharat’ is extremely informative as it gives example of reasons of Bhils turning to gangs of looters and rebels as the old kingdoms left them unattended during the time of massive drought and famine killing hundreds of people and compelling them to fend for themselves. Bhils were becoming rebels because of their socio-economic condition and exploitation. They were witnessing death and yet never lost fighting honorably. In 1823, as many as 172 Bhil prisoners out of 232 who were sent from Khandesh died during the journey which reflected the behaviour of the police towards them.

Bhil Revolts

The first Bhil revolt happened in 1804 against Peshwas who as mentioned earlier too were brutal and criminalising Bhils. Prior to British taking over, Bhils fought against the local chieftains, caste prejudiced Rajas and Majarajas who were exploiting them. The book document important heroes of Bhil rebellions such as Nadir Singh Bhil (1802-1820), Gumani Nayak (1819-1820), Cheel Nayak, Dasharath and Kania revolt in 1820, Hiriya Bhil, 1822 and Bhari Bhil 1824. All these are well narrated.

There are numerous other stories ranging from Mulher (Nasik, Maharashtra) historical battle of 1825 till Kunwar Jeeva Vasava in 1846, which also explain how the English tried to divide Bhils on religious lines, as Muslim Bhils were more aggressive and rebellious in nature.

But two important things need to be understood to identify the Adivasi rebellion in India and why the British had actually soft corner for them. The first thing is that Adivasis were fighting to protect their own land from outsiders and for them, whether it is Indian outsiders or British, did not matter. However, the British too wanted to exploit their natural resources. Adivasis in India have always revolted against any attempt to change the nature of their life style and culture. British wanted to exploit the forest resources and wanted to push their ‘citizenship agenda’ everywhere. The census operations started for the purpose of identifying people and resources so that everything is documented. In 1852, land survey was ordered in Jal Gaon area as East India Company wanted to push through its new revenue model and forest was an income generating or revenue generating model for them. There was massive revolt against the British in 1853 and 1858 against their exploitation of the local resources.

An interesting part in this is that rest of India was also revolting against the British policies but Adivasis and Dalits were always maltreated by those who were claiming discrimination from British. That was the irony that the initial anger and rebellion among Dalits and Adivasis was mainly against the feudal lords who were exploiting them and treating them worse than animals. Subhash Chandra Kushwaha has already brought this aspect in his two-landmark work, ‘Chauri Chaura Revolt and Freedom Movement’ (now available in English too) as well as on ‘Avadh Kisan Vidroh’, gives the other side of the history which has been neglected by the historians. All these movements subsided in the nationalist war cries of Gandhi and Congress party which assimilated them and converted the entire issue as the fight against British Raj. Ignoring the local feudal caste culture was the biggest drawback of Gandhi’s movement though he symbolically tried to address the issue of ‘untouchability’ without attacking the caste system which made it a complete farce.

The second part of the book is focused on Rajputana, Revakanta and Mahi Kanta agency which give us details about the geographical location of the region followed with an analysis of Rajputs and Bhils of Rajputana. Rajputs and Bhils had complex relationship and perhaps historians can work further on the issue particularly in Rajasthan where Rajputs are particular about their historical heritage and mention Maharana Pratap as an extremely benevolent ruler and friend of Bhils. Revakanta was an agency in Gujarat and Mahi-Kanta in Bombay Presidency where Bhils lived in large number and revolted against British policies of acting against Bhil Jagirdars and the military action in 1820 hardly got any success and were able to contain the rebellion to some extent by December 1823.

A separate chapter is on the icons or heroes of Rajputana, Revakanta and Mahi Kanta Bhil revolt beginning with Baroda Bhil revolt in 1804. The first among those heroes by Jagga Rawat (1817-1830) who rejected the domain of the Rajput kings and was arrested on February 27, 1826, and was kept till 1830. But not much is known about his condition later on. Another interesting documentation is the Banswada Rebellion (1872-1875) led by Dalla, Deva, Onkar Rawat and Anupji Bhil. This is explained in a better way which says that the pact in 1868, between Banswada State and the English got the right to suppress Bhils and exploit the natural reserve in those areas. There is also a short yet interesting description of Mewar Bhil Revolt of 1881 but heroic fight of Govind Guru at Mangarh Tekari in the Dungarpur province in 1913 is narrated in extreme details and how the British finally neutralised the Bhils in the region. It was unambiguous that Bhils were revolting against exploitation and refused to do slave labor. There was campaign against alcoholism as well as for vegetarianism, monogamy and against dowry.

Tantya Bhil

In the third part of the book, a biographical sketch of Tantya Bhil who was referred as The Great Indian Moonlighter by foreign media. He was a rebel with a cause and most ferocious who got a Robinhood image as he was a messiah for the poor. Born in 1842, Tantya saw exploitation from the childhood as his ancestral property was illegally grabbed by local feudal lord whose caretaker was killed by Tantya. He was arrested in 1873 and got one year imprisonment. Tantya continued his fight against exploiters and have been in and out of jail for so many times. Since 1878 to 1888 Tantya had over 400 cases of dacoity against him but he was never caught. Police always disturbed his relatives and other family members. Tantya was finally arrested on August 11, 1889. On October 19, 1889, Tantya was sentenced to death by session Judge Lindse Niel in Jabalpur. On December 4, 1889 Tantya was hanged to death inside the Jail.

Though this book itself has a big chapter on Tantya Bhil, Mr Subhash Chandra Kushwaha is writing a separate book on Tantya Bhil.

This book is extremely important to understand the history of Bhil revolt in India though I would say that it is an entry point for future generations to know in details but as a person keen to understand the viewpoint of those who have been denied spaces and deliberate omissions by those suffering from prejudices, it is advisable that attempt should be made to find the local narrative about these incidents. As most of the documentation or references in this book emerge from various archives or international media, there should be an Adivasi side of it too and to explore that it would be good to visit some of these places and document the oral history of the region so that we get the ‘other’ side of the narrative particularly prior to British period as well as during that period.

Subhash Chandra Kushawaha is working on these issues passionately and voluntarily for the last so many years. It is his zeal that made him do this extremely difficult task of documenting things from various archives and libraries. Researchers in the Universities and institutions should now follow it up and dig the Adivasi history further so that they get a fair deal. We need more and more such initiatives particularly from Adivasi communities and their scholars to take this further towards a logical conclusion.

Name of the Book: Bhil Vidroh: Sangharsh ke sawa sau saal

Author: Subhash Chandra Kushwaha

Publisher: Hind Yugm

Pages: 352

Price: Rs 249