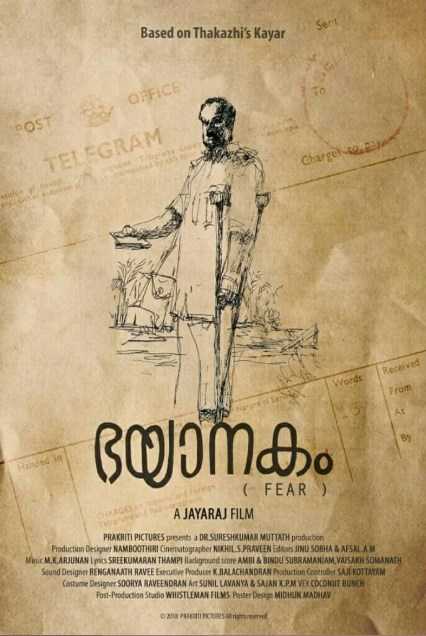

Director Jayaraj brings together the consequences of war and the stories of the colonised

Image Courtesy: IMDb

A First World War veteran begins life as a postman in Kuttanad, a small village by the backwaters of Kerala. The Second War is about to begin. Young men from the village, like others across the country, are enlisting in the colonial army. Many have already joined and gone to their postings. He paddles around in his little boat delivering money orders sent by the soldiers to their poor tenant-farmer families. For those who live by the whims of rich landlords, the money is a godsend and the postman a good omen. Maimed from the war and supporting himself on a crutch, gently dismissing the blessings gushed on him, he is the only person who has actually lived through a war. Small children talk excitedly of killing unknown enemies, the young are desperate to compensate their families’ meagre finances, the old are just grateful to not be entirely at the mercy of landowners and the weather. The postman watches all this worriedly.

Director Jayaraj’s Malayalam film Bhayanakam fills a gap in the grand chronicles about the Second World War that are painfully incomplete – the histories of those who fought, served and died at the behest of their colonisers, unthanked and largely forgotten. Similar omissions occur of the role that African-American men and women played in the War. In her article, “African-American GIs of WWII: Fighting for Democracy abroad and at Home,” Maria Höhn writes: “Until the 21st century, the contributions of African-American soldiers in World War II barely registered in America’s collective memory of that war. The ‘tan soldiers,’ as the black press affectionately called them, were also for the most part left out of the triumphant narrative of America’s ‘Greatest Generation’.”

Films like Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk use visually stunning cinematography to peddle a false narrative about the “plucky little country defying the massed ranks of fascists and Nazis”. As a review of Yasmin Khan’s book The Raj at War highlights: “The British always liked to believe they stood alone in 1940 … Britain did not fight the Second World War, the British Empire did.” That this empire’s colonies were a steady supply source of impoverished men fighting for a living is conveniently left out from big-budget Hollywood takes on the War. What could Europe and America’s war have possibly meant to those soldiers? What could “fighting for freedom” mean to those living under the multiple oppressions of colonialism, caste and race? Dunkirk ended with an archival recording of Churchill’s speech in Parliament (that alone is a sign of its exclusionary politics): A British hero, Bengal’s oppressor and a racist. A man responsible for the Bengal Famine (1943) that killed close to four million, because food grains were diverted to British soldiers instead — genocide.

Telling a fragment of this history, through the people of a small village in British India, Jayaraj brings together the consequences of war and the stories of the colonised. As the film proceeds, the money orders dwindle and the death notices increase. The goodwill that the superstitious villagers had towards him turn to fear and loathing. To them, he is a grim reaper— a sign of death in the family. They flee his presence, curse him, even beat him, seeing in him a corporal cause for their confusion, grief, rage and terrible loss, rather than the distant war they don’t understand. Their son is dead; so says a brusque telegram they can’t read, on which a name and the word “expired” are printed. He must read it to them. It’s his voice delivering an irreversible truth, if he didn’t speak those words, their son would still be alive. But the postman must do his job, so he plods on, grieving each death with them.

The sweeping rain and the lush landscape of Kerala’s gorgeous backwaters, bleed colour as the death notices pile up, until everything is dull and lifeless. Renji Panicker who plays the postman is at first soft-spoken and mild, but becomes increasingly broken and tormented. Asha Sharath’s character rents him a room in her small house. She has both sons in the army. She saves up all the money they send her, hoping that they will be comfortably off when they return. She and the postman grow to care for each other and she confides her fear of their deaths in him. Each day, he in turn fears that a fresh batch of letters would also mean informing someone he loves, that she has lost her sons. Sick with anxiety, he becomes trapped in his own world of past trauma from the war, nightmares and a terror of the death notices that arrive with almost daily frequency.

Bhayanakam is the sixth film in Jayaraj’s “Navarasa” series. This film, as its title suggests, centres on fear. The previous films from the series are Karunam, Shantam and Bheebhats (made in Hindi), Adbhutham and Veeram. He hopes to finish the series with films on the remaining rasas – sringaram, roudram and hasyam. The story is adapted from two chapters of Malayalam novelist, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s book, Kayar. The novelist carried the place of his birth in his name. As a nod to the film’s resource material, when the postman is asked where he’s from, he replies that he’s from Thakazhi. Bhayanakam has won the National Film Awards for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay, the Vijay Award for Best Music Director and the Kerala State Film Award for Best Processing Lab/Colourist. It was screened recently at the India International Centre, New Delhi as part of the Malayalam Film Festival (03-06 July) curated by film editor and artistic director of International Film Festival of Kerala, Bina Paul.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum